The Magickal World of Hilma af Klint

A brief history

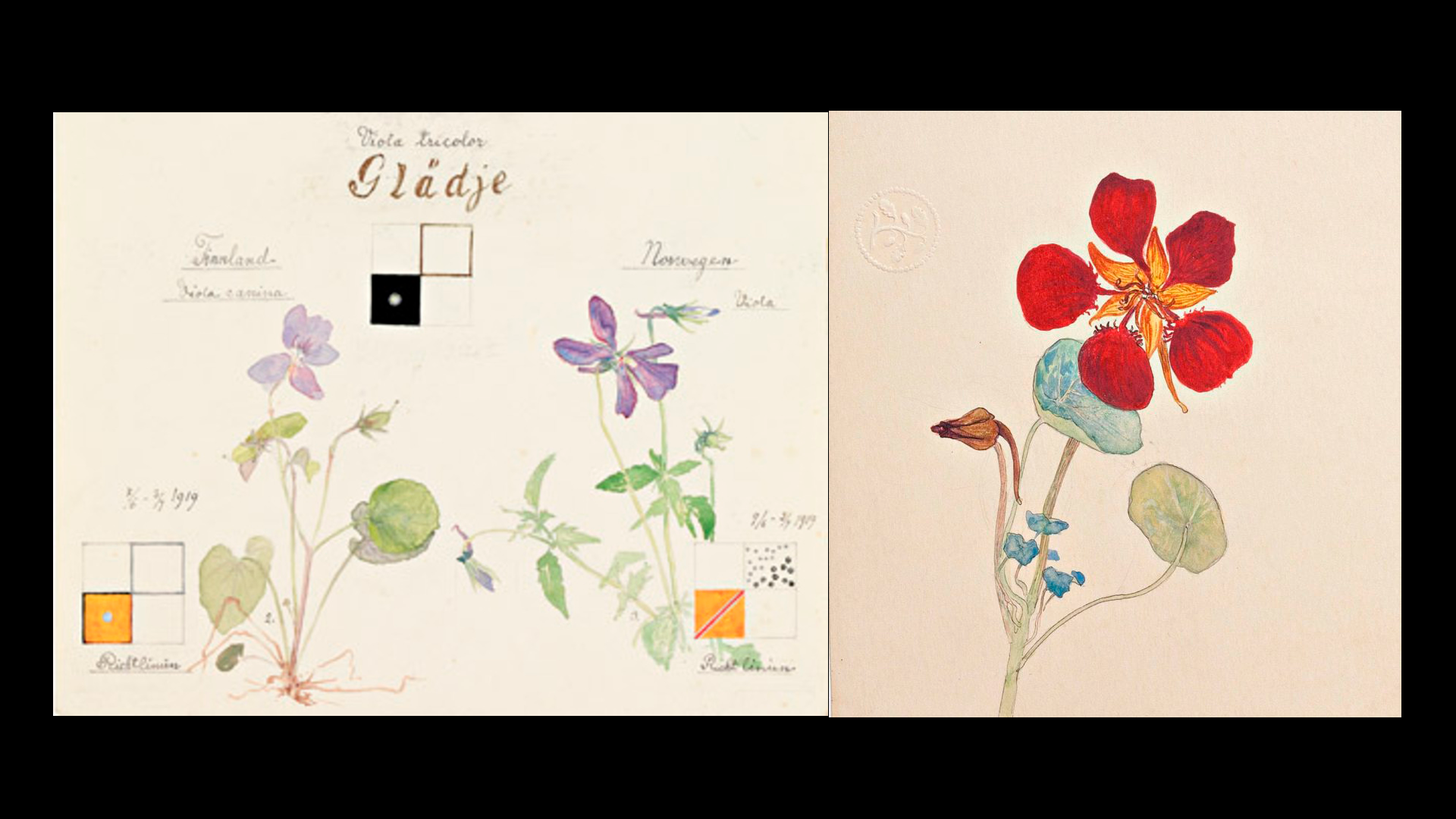

Hilma af Klint was born in Sweden in 1862 into a fairly middle class family. She was interested in botany and maths from a young age and she spent a lot of time in nature being inspired by natural forms. She enjoyed painting nature and creating botanical drawings - which you can see carrying through her later art practice. She studied at the Royal Academy of Art in Stockholm; concentrating on portrait and landscape painting. After graduating with honours she made something of a name for herself and her painting was even a source of income for her.

When she was 18 her younger sister died and this was when she started to take an interest in the spiritual as she sought to find meaning in life and death. She became interested in Theosophy – a wildly influential spiritual system generated by one Madame Blavatsky in 1875 – as well as spiritism in general which was wildly popular in Europe at this time being concerned with mediumship and the spirit world.

After completing her art school education she formed a group of women called The Five, all interested in the paranormal and mysticism. Through ritual practices they recorded in a book a system of mystical thought, in the form of messages from higher spirits called The High Masters. The Five experimented with automatic drawing and use of geometry as a visual language to conceptualise the unexplainable – this in itself isn’t a new idea, but something that has been traditionally used in esoteric practice.

Af Klint felt she was being guided by a force she didn’t quite understand. It directed her to create paintings for a Temple, but she was unsure what this meant and what this temple was meant to be. In her note book she wrote:

“The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

It was her art practice combined with her interest in the otherworldly that came together to allow her to create some of the most extraordinary work of the early modernist era – making abstract painting in 1906 - 5 years before the 1911 date claimed by Wassily Kandinsky as the first ever piece of abstract art.

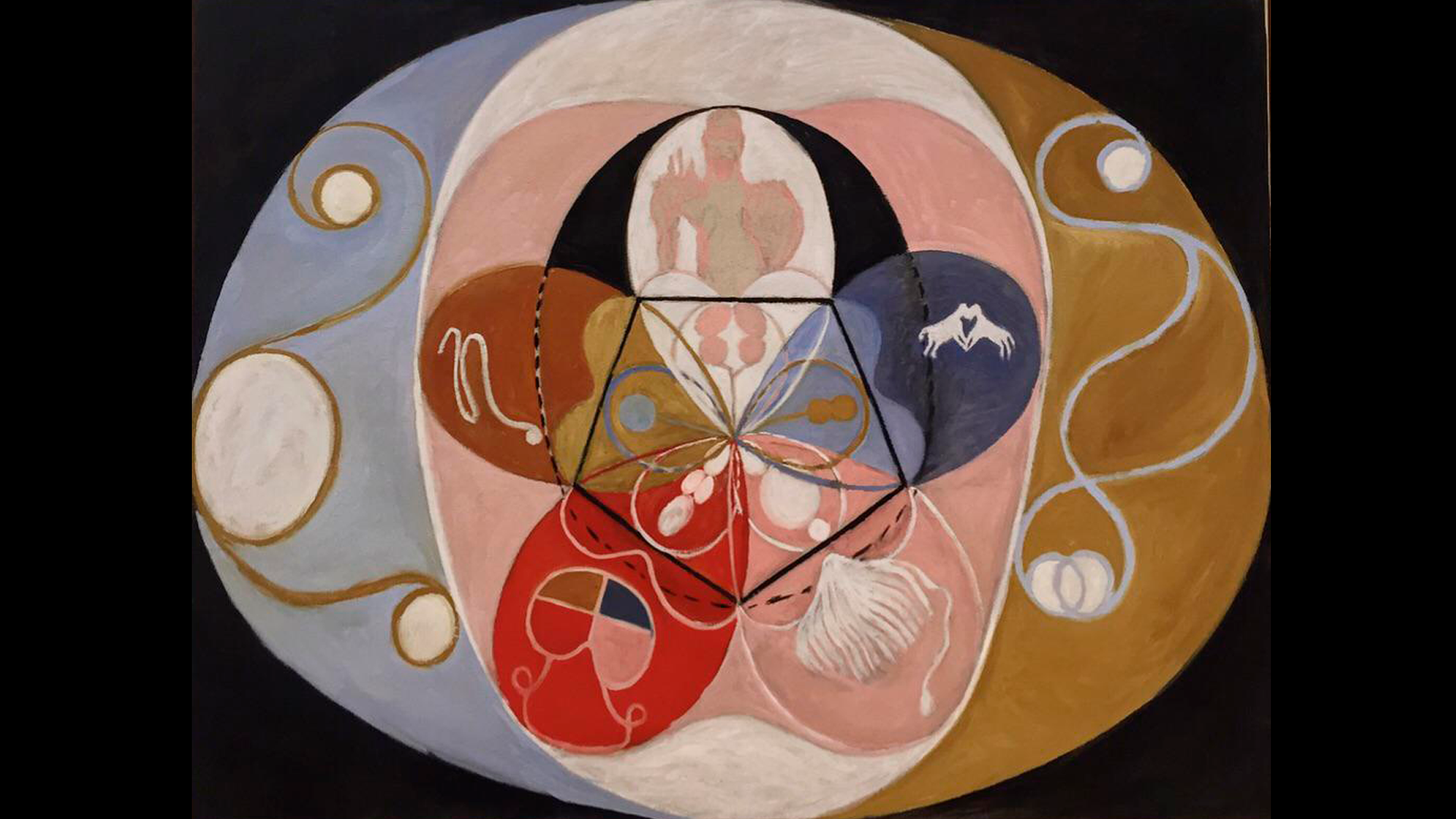

The works for the Temple were started in 1906 consisting of 193 paintings, grouped within several sub-series. The major paintings called the Ten Largest are extremely large and describe the different phases of life, from early childhood to old age - personally I see them as a kind of Initiatory process. They are filled with symbolic meaning and diagrammatic language, with colours, letters, shapes all serving a narrative and descriptive purpose. It seems that the abstraction in her work served to transcend the physical world and the constraints of representational art so that she could communicate the incommunicable.

When she had completed the works for the Temple, the spiritual guidance she was receiving ended. But she continued working with abstract painting, now entirely directed by her own creativity. The works were not to be broken up - they needed to be shown all together, so she did have plans on how to build the temple to house the paintings, but unfortunately this never came to fruition. Interestingly her design bears similarities to the spiral shape of the Guggenheim gallery where she had her most successful posthumous exhibition.

Throughout her life af Klint kept many notebooks – 150 in total. The ones she created to accompany her Temple work help to decode her visual language, but they are also obviously assisting her in to trying to understand what she was creating. This is fascinating to me because it speaks to the authenticity of the creation – she obviously truly felt that the inspiration was coming from outside of her, there is no sense that she is deceiving or trying to claim something she does not believe herself.

I think it’s important to note at this point that Af Klint was not an outsider artist. She had an art school pedigree, was aware of contemporary art and the artists creating it. As far as we know she was not suffering from any mental disturbances and she was able to be part of society. It’s easy for the viewer to look at this strange, almost incomprehensible work and assume it came from someone divorced from the art world and maybe to some extent from reality – but that is not the case.

My thought’s on af Klint as an esoteric artist

‘Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future’ Edited by Tracey Bashkoff (Guggenheim Museum Publications; New York, USA) has an essay which is the transcript of a conversation between 7 artists, curators and art historians. I wanted to respond to some of their questions and the theories they put forth. Obviously this is purely my take on the subject, but it’s pertinent to me as someone who is straddling the art world and the occult world. There are some fascinating discussions to be had about this kind of art and it’s place in the contemporary western art canon:

The first point is made by Amy Sillman who states that when she went to see the work at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm she talked with a teacher from the Royal Academy who made the statement that af Klint “is not an artist, she’s some sort of mystic”.

This statement is of particular interest to me as it’s a sentiment that I’ve also had levelled at my own work. It’s been postulated to me that perhaps art wasn’t the best way to express my ideas, which seemed a very odd stance to take seeing as art has been a conduit for mystic of spiritual expression for thousands of years. I don’t see why contemporary art critique has spuriously created this division in the last century. In point of fact af Klint follows all the rules for being considered an artist and not an outsider with her art school pedigree, lifelong practice and familiarity with contemporary art movements.

Leah Dickerman suggests that the issue is that af Klint maintained she was receiving the images from ‘somewhere else’ rather than constructing a sustained theory of representation like Kandinsky. While I understand the point being made, I feel that it’s taking art to a purely academic place which therefore excludes whole areas of expressive exploration and diminishes rather than elevates the scope of an artists practice. It wasn’t as if she came to this work without an ongoing practice and an art pedigree.

Western contemporary culture is very secular these days - which overall I feel is a positive thing - and of course that is reflected in contemporary art and academia. While the western-centric art world seems to be finally relaxing it’s hegemony, leaving space for and even starting to encourage artwork which explores different cultural ways of knowing from around the world, it seems to struggle immensely with work created by western artists which examine the same kinds of alternate ways of knowing but from a western cultural perspective. It’s almost as if theirs a western art world cultural cringe about being born out of religious painting! I believe this is a curious stance considering the immense popularity of af Klints overtly esoteric artworks. Perhaps its ok to acknowledge that there is a craving in secular Western society for this kind of experience?

The next interesting point discussed in this conversation is her studio visit from Rudolph Steiner. Austrian born Steiner had his own spiritual movement ‘anthroposophy’ and was heavily influenced by Goethe as well as Theosophy and Spiritism. I guess he was kind of a ‘Big Deal’ because he had a lot of success during his lifetime and we still have Steiner schools to this day. He formulated a path, a theory and put it out in the world to be followed. – instead of saying here are some ideas to examined he said ‘I have a way and an answer’ which is a risky thing to do and doesn’t leave much space for questioning. I’m going to be quite honest and say I don’t rate Steiner at all and I imagine him to be pretty egotistical despite his spiritual proclivities, so this anecdote told in the conversation from the book didn’t particularly surprise me:

He visited Hilma in her studio in 1908 where she proudly showed him her finished ‘Paintings for the Temple’. She was an admirer of his work and so I think his opinion would have meant a lot to her. Unfortunately he was less than enthused with her art or her mediumship. Lisa Florman suggests that Steiner probably wanted to bring her work inline with his own brand of spirituality, seeing her as a big of a wild card off doing her own thing. It also seemed that he doubted her mediumship which suggests he thought her claims of otherworldly instruction were outright lies.

Anyway, this studio visit from Steiner caused af Klint to stop painting for 4 years. He had tried to steer her creativity in a direction that he felt was more appropriate and thereby killed off her impetus to paint. Anyone who has had an unpleasant critique at art school knows what this can be like. No matter how confident and autonomous one might be, having someone you respect rubbish your work is a belittling experience.

Interestingly enough, Steiner kept photographs of some of af Klint's work and later the same year he met Wassily Kandinsky, who had not yet come to abstract painting – which leads to the supposition that Kandinsky could have seen the photographs and perhaps was influenced by them while developing his own abstract work.

Further on in the conversation Anne Sillman expresses the fact that RH Quaytman described af Klint in a way she hadn’t thought of before; as a translator. For me this was an immediately obvious description of what af Klint does. Take something that cannot be described or explained and find a way to describe and explain it. For people coming to her work from an art historical or contextual standpoint, the work can appear unmoored and without points of art historical reference to work from. But to people coming from an occult standpoint there are many familiar clues to the language she is using and what she is translating. Much like the fact she isn’t an outsider artist but is grounded in the language of art, the same is true of her grounding in western esotericism, it hasn’t leapt fully formed out of thin air.

That is, apart from the paintings known as the Ten Largest, I find these images are the farthest removed from any familiar visual language, which is perhaps why they are also so very beguiling for so many viewers. I thought it would be interesting to look through some of af Klints work where I found reference to familiar western esoteric themes. I’ve found some images from pre-Enlightenment to Enlightenment era manuscripts that I really like and feel give quite a nice idea of historical esoteric thinking where the artists were perhaps trying to ‘translate’ an idea with intrinsically mystic content.

A comparison to some Enlightment era manuscript art

On the left are 2 images from her 1913 Tree of Knowledge series. The forms and colours have quite a art nouveau feel. The symbolism seems to draw from mystic Christianity. She’s got a progression up or down the length of her tree with a chalice at the apex of both and divisions into different spheres or regions. You can see that she has visualised the movement perhaps of some sort of energy.

The third image along is Athanasius Kircher’s 1652 depiction of the Tree of Life which is a diagram used in hermetic kabbalah and derives from Hebrew mysticism. On the right is a 1785 manuscript page showing the tree of knowledge of good and evil. You can see in these the way a diagrammatic method is used to illustrate and explain metaphysical ideas. They both show and emanatory system using spheres and pathways that represent the incorporeal.

These 2 paintings on the left are from the 1915 series – The Dove; number 1 on the left and number 9 on the right. I love how delicate and ephemeral these paintings are. Again you can see the mystic Christian and Rosicrucian symbolism at play, as well as the upwards/downwards spiral movement extant in her Tree of Knowledge paintings.

The images far right are examples of The Dove and how it appears in western esoteric art – it’s a very popular motif with the dove’s appearance in both the old and new testament. On the left is a 16th Century alchemical drawing showing the marriage of the sun and the moon where you can see the dove moving down towards the intersection of their union. On the right is a 15th Century alchemical drawing which I like especially because it echoes the gentle watercolours used by af klint in many of her later starkly abstract works.

A couple of af Klints later abstract works; On the left Series 8 On the right Series 7 Number 7 from 1920. On the far right some early 16th Century Alchemical drawings. They don’t have the beautiful colours used by af Klint and they ARE actual diagrams – hence the text – but they show the provenance of geometry in esoteric art. You can see a bit of colour use in the cross at the top of the right hand page and this will certainly have symbolic meaning in the choices of colour.

Af Klint’s use of colour as part of her symbolic language is line with what I have seen from other artist’s at the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th Centuries as Ithell Colquhoun who were interested in the magical potential of colour as new brighter, clearer pigments became available.

After looking at these fascinating geometric diagrams it’s the perfect time to view af Klints 1915 altarpieces which were part of her Paintings for the Temple. I think these are just absolutely stunning and solidify her in my mind as the natural successor to the esoteric art tradition.

And finally her Ten Largest from 1907 which I think are the most unusual and unique of her major works. In these I can’t see the influence of anything that has come before, which is what I meant when I stated that I felt her belief in the provenance of the work was authentic. She believed that she had been instructed and it seems she used the visuals tools she had available and that she was most comfortable with; her botanical and nature studies, her love of colour as a visual language. She was translating something for us, although she herself wasn’t too sure what the message was. It does appear to resonate with many, considering the popularity of her exhibitions.

As you can imagine I’ve read many articles, reviews and pieces about Hilma af Klints work. Something I see throughout many of them is a tendency to cringe a little over the reason and motivation behind her paintings. The art world are at the same time fascinated by and embarrassed of her esoteric inspiration. I would love for this to gradually fade away and for her to be talked about as a whole being, with her work and her mysticism unapologetically embraced. Her mysticism doesn’t need to be treated like a slightly embarrassing personality quirk and it doesn’t matter if the viewer, the reviewer, the writer believes her or not – it’s irrelevant. What she has created – or translated – stands on its own merits. And let’s face it, none of it would exist without her mystic exploration, you’d just have another reasonably decent Swedish landscape artist faded into obscurity.