Texts.

Photographers Pay Homage to Occultist

Mark Amery : 22 May 2021 : Te Hikoi Toi : Dominion Post

Contemporary art sings when it challenges the familiar, encouraging understanding of things gleaming just outside our radar.

Visiting galleries, my assumptions are regularly challenged. The trick, I suspect, is to be curious, avoiding something easier to slip into: feeling dumb.

I’ve been working on expanding my mind, and this week I visited two exhibitions crossing quite different lesser-known realms, with artists I didn’t know.

British painter, writer and occultist Ithell Colquhoun (1906-1988) is a 20th-century woman just starting to gain attention. Communicating Vessels, at Wellington’s home of photography, Photospace Gallery, sees three strong photographers pay homage to Colquhoun’s life and work.

After gaining attention in the British Surrealist Group in the late 1930s, Colquhoun was banned from the group for refusing to renounce affiliation with occult groups. She shifted to work in Cornwall, entering relative obscurity. But times may be changing: In 1999 the Tate bought the National Trust’s collection of her work.

In this exhibition, featured is a set of her small abstract enamel works on paper, made for a book for contemplation. Decad of Intelligence is based on 10 ‘‘sephirotic intelligences set out in the Kabbalistic text Sepher Yetzirah’’. Whew, that takes some unpacking. These are emanations said to come from the metaphysical realm, as identified by this Jewish school of mysticism. Each has different colour scales, associated with different life forces, corporeal and spiritual. Fascinating, yet as artworks underwhelming next to other Colquhuon work, seen in reading material.

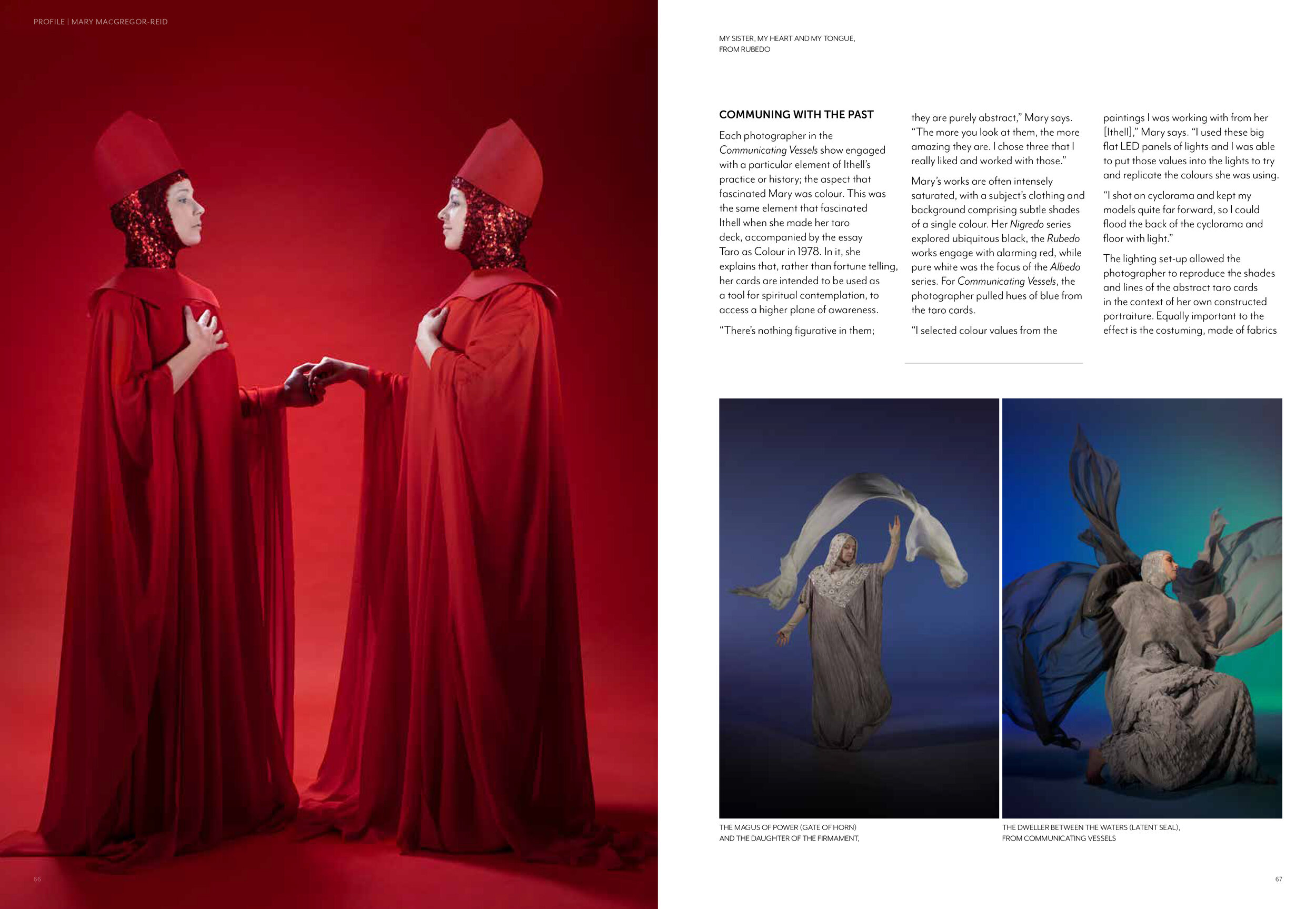

Stronger are the works of the three photographers, each providing performances; communion and ritual with unseen forces, captured by camera and then altered by photography’s own alchemical magic.

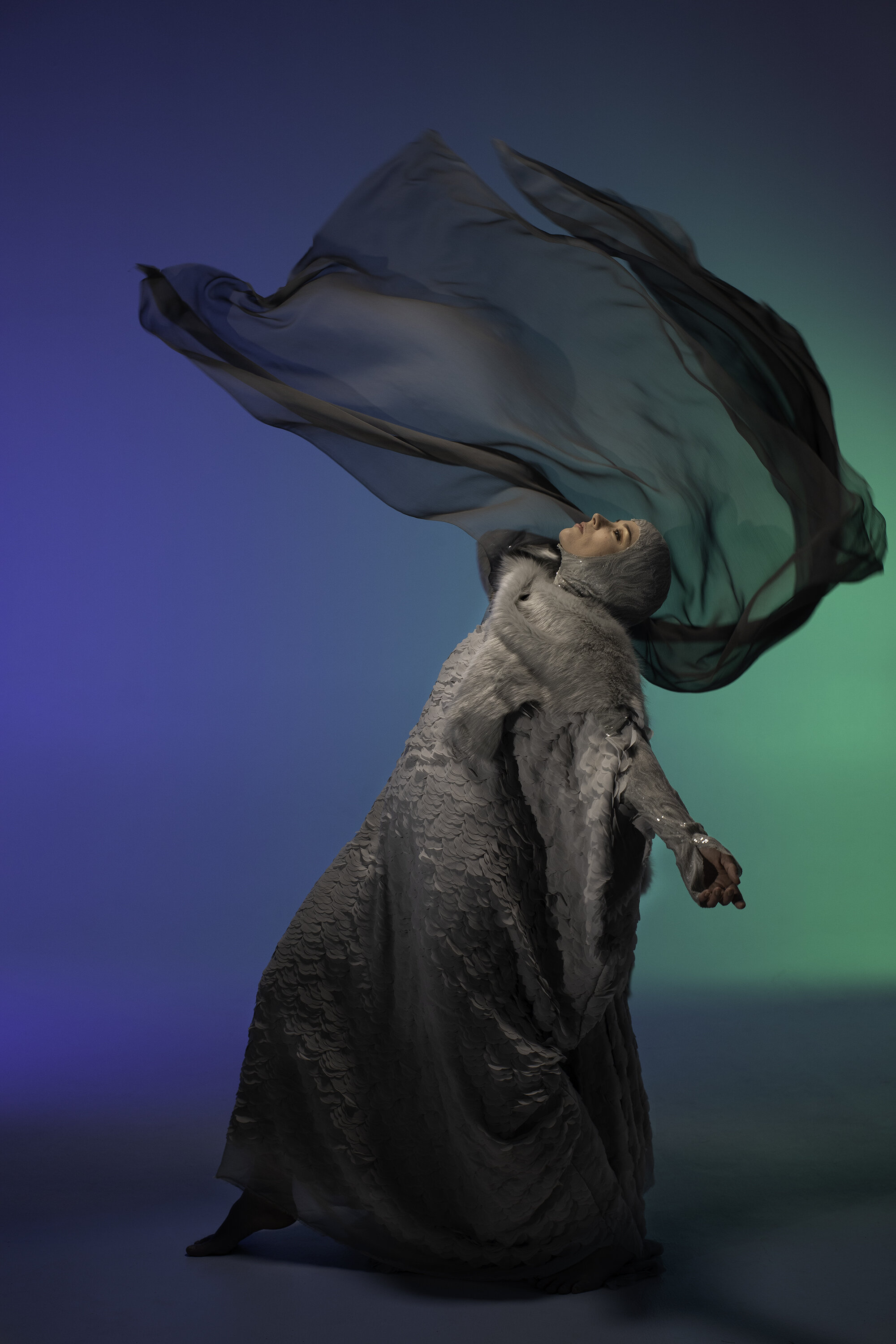

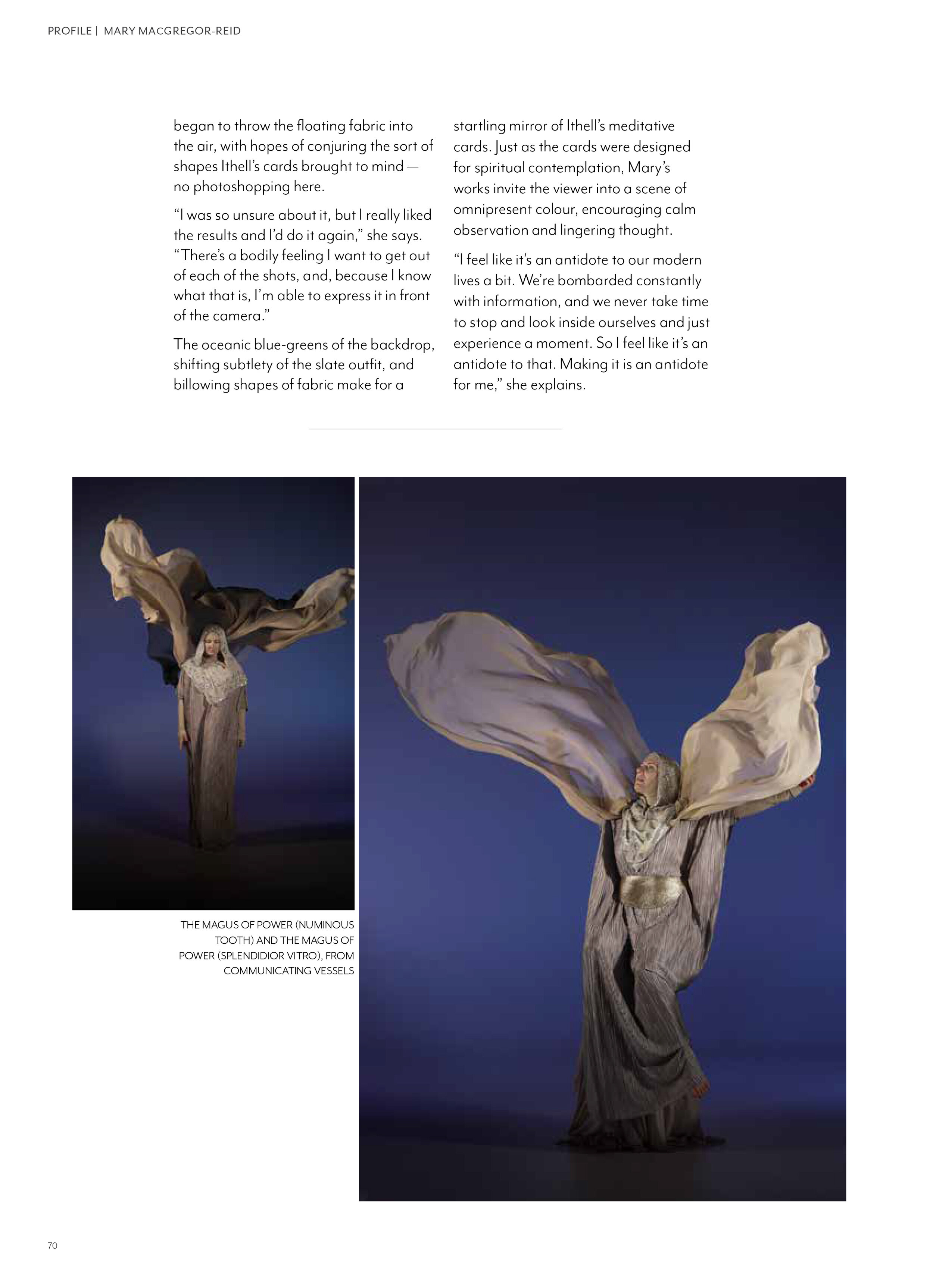

Mary MacGregor-Reid’s work is inspired by abstract tarot cards made by Colquhoun, which have remarkable swirling colour and galactic starbursts. A dancer in sparkling ivories and greys performs in a revelry before a studio backdrop of green and purple that resembles the aurora (long associated with the secret occult society of the Golden Dawn). There’s rich layered costuming of furs and fabric, with scarves caught floating voluminously in the air like spiritual hosts. The woman is in control, echoing the poses of empowered female figures across religious iconographies.

Mary MacGregor-Reid’s work is inspired by abstract tarot cards made by Colquhoun, which have remarkable swirling colour and galactic starbursts. A dancer in sparkling ivories and greys performs in a revelry before a studio backdrop of green and purple that resembles the aurora (long associated with the secret occult society of the Golden Dawn). There’s rich layered costuming of furs and fabric, with scarves caught floating voluminously in the air like spiritual hosts. The woman is in control, echoing the poses of empowered female figures across religious iconographies.

A Colquhoun painting that depicts submerged Neolithic standing stones in Brittany is the inspiration for Hayley Theyers’ work. They’re set in a surreal underwater world, alluding to environmental degradation and a diseased kauri forest on the Manukau Harbour. In Colossus, kauri with leaves and, perhaps kelp, is suspended, golden like gum, in ice. Melting menhirs, they are rich in mysterious textures as if they might in the next moment come bird-like magically alive. In other works, a figure struggles under water, with the brackish glow of leach from the forest. I’m reminded of Christine Webster’s photography.

Kate Rampling’s delicate black-and-white photography of figures in landscape engages with surrealist automatism techniques, with stone and fire meeting on the surface of her negatives. Elsewhere, simple materials elegantly twist into charged yet enigmatic symbols, as if by spells.

When and where Communicating Vessels; Photospace; until June 26.

Right, work by Mary MacGregor-Reid, from Communicating Vessels, now on at Photospace Gallery; left, Hayley Theyers’ work is inspired by an Ithell Colquhoun painting that depicts submerged Neolithic standing stones in Britanny.

The Laws of Ordinary Existence Do Not Apply

Adrian Hatwell : Issue 98 Summer 2021 : D-Photo

A lost artist of the 20th century is conjured back to life by Auckland photographer Mary MacGregor-Reid as she mixes colour and the occult in a breathtaking new series.

The colours seem to bloom and roil within the frame. Flares of turquoise punctuate tracts of cold teal, clots of periwinkle surrounded by deep midnight set off small canary tendrils; the images look like they could be the cross-sections of some alien sediment or darkly psychedelic weather maps. They are in fact images from an unconventional tarot deck. Where tarot cards are often used to divine information about the past, present, and future, these ones encourage contemplation and offer a path to higher planes of thought.

That was the intention of their creator, Ithell Colquhoun, an underacknowledged female artist in early 20th century Britain. A painter, writer, and occultist, Ithell’s work was associated with British surrealism until her more esoteric interests were said to have seen her rejected by the movement. Much of her work, such as her taro deck — she drops the second ‘t’ in ‘tarot’ to associate more closely with the cards’ Egyptian heritage — employed automatist techniques designed to bypass consciousness and access something other. In Ithell’s case,she hoped to tap into cosmographic rhythms and the natural energies of the universe.

Whether it was because of her mystical leanings or simply the fact she was a woman, Ithell’s large body of work — which includes large-scale biblical paintings, botanical watercolours, automatic paintings, drawings, collages, murals, and more — was little known in her time and remains largely so today. However, a number of admirers around the world are now attempting to cast light on this overlooked legacy and bring about the posthumous recognition the artist deserves. Among those ranks is Mary MacGregor-Reid, a contemporary photographer from Auckland with her own taste for the occult.

“She’s this amazing artist and occultist who is just starting to be brought into the light, along with those other modernist women artists who were written out of history,” explains Mary. “We all just fell in love with her so much.”

A PECULIAR HISTORY

The “we” of who Mary speaks are herself and fellow photographers Hayley Theyers and Kate Rampling, who together created the Communicating Vessels exhibition, inspired by the works of Ithell Colquhoun. Hayley’s dreamy melodrama and Kate’s dark expressionism mingle with Mary’s own ritualistic colour to create a multifaceted tribute to the diverse career of their inspiration.

“When we were coming up with the concept for the show, we thought it would be great to choose a woman artist and be inspired by her,” Mary explains. “We all have a bit of an esoteric link and are interested in that side of things, so she was just perfect.

“The cool thing was, we were all deeply enamoured by a different aspect of her and her work. So our work came together as a whole, but it was still very different and addressed different aspects of her.”

Mary’s own connection with Ithell turns out to be somewhat personal. As a teenager she found herself drawn to the occult, reading up on all manner of esoteric topics. When her father discovered this passion, he revealed some family information that his daughter had previously been unaware of: both her grandfather and greatgrandfather were part of the ancient order of Druids in England. Mary has been researching their history ever since.

“My grandfather is this really weird character; he’s so eccentric and hard to pin down,” she says. “He made all these insane claims, like that he travelled through Tibet as a monk and he’d been a ship’s doctor in the Antarctic — all sorts of crazy stuff.

“I found these other interesting people in the UK who were researching him as well, and we discovered that quite a few of these wild claims he made sound like they could actually be true.”

Grandfather George Watson MacGregor Reid was particularly notable in these circles, being a member of Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn secret society and an acquaintance of Aleister Crowley, perhaps the 20th century’s most famous (or infamous) occultist. The photographer’s research eventually brought her to England,where she was granted access to The Warburg Institute, associated with the University of London. It is a unique library dedicated to the intersection of art, science, and history with mysticism, superstition, and magic. There she was able to peruse many original manuscripts held by occultists of the past, including correspondence penned by her grandfather. It was there she also discovered the forgotten legacy of Ithell Colquhoun.

COMMUNING WITH THE PAST

Each photographer in the Communicating Vessels show engaged with a particular element of Ithell’s practice or history; the aspect that fascinated Mary was colour. This was the same element that fascinated Ithell when she made her taro deck, accompanied by the essay Taro as Colour in 1978. In it, she explains that, rather than fortune telling, her cards are intended to be used as a tool for spiritual contemplation, to access a higher plane of awareness.

“There’s nothing figurative in them; they are purely abstract,” Mary says. “The more you look at them, the more amazing they are. I chose three that I really liked and worked with those.”

Mary’s works are often intensely saturated, with a subject’s clothing and background comprising subtle shades of a single colour. Her Nigredo series explored ubiquitous black, the Rubedo works engage with alarming red, while pure white was the focus of the Albedo series. For Communicating Vessels, the photographer pulled hues of blue from the taro cards.

“I selected colour values from the paintings I was working with from her [Ithell],” Mary says. “I used these big flat LED panels of lights and I was able to put those values into the lights to try and replicate the colours she was using.

“I shot on cyclorama and kept my models quite far forward, so I could flood the back of the cyclorama and floor with light.”

The lighting set-up allowed the photographer to reproduce the shades and lines of the abstract taro cards in the context of her own constructed portraiture. Equally important to the effect is the costuming, made of fabrics and textures that reference the structure of the impressionist taro cards in fabric form.

“I make all of my costumes — that’s part of the process for me,” she says. “I feel I am dressing the characters who are going into the work. The meditation of making them is part of it as well.”

While she has no formal training in costume making, Mary’s background in Auckland’s goth music clubs and contemporary dance have given her plenty of experience in the craft. Her subjects are typically friends who volunteer for projects, masked almost completely by the covering garments.

“I’ve hardly worked with professional models, but when I have I find they are almost too focused; they’re not relaxed enough,” the photographer explains.

“Whereas with my friends I can just say ‘Stand there’ and they will literally just stand there, which is perfect. I’ll come over and move their hand and they’ll just stay there; they don’t feel the need to pose. I love these natural stances. I do put them in strange positions, but at the same time they have this really relaxed, normal look.”

BEST-LAID PLANS

For Communicating Vessels, Mary had to tweak her usual process due to the first, sudden Covid-19 lockdown earlier this year. A friend had originally been drafted for the shoot, but the incoming restrictions didn’t allow for anyone outside of the photographer’s bubble to be in the studio. The way forward was clear; Mary would have to step in front of the lens herself.

After dialling in the settings, she left her husband to trigger the camera as she donned her elaborate costume and began to throw the floating fabric into the air, with hopes of conjuring the sort of shapes Ithell’s cards brought to mind — no photoshopping here.

“I was so unsure about it, but I really liked the results and I’d do it again,” she says. “There’s a bodily feeling I want to get out of each of the shots, and, because I know what that is, I’m able to express it in front of the camera.”

The oceanic blue-greens of the backdrop, shifting subtlety of the slate outfit, and billowing shapes of fabric make for a startling mirror of Ithell’s meditative cards. Just as the cards were designed for spiritual contemplation, Mary’s works invite the viewer into a scene of omnipresent colour, encouraging calm observation and lingering thought.

“I feel like it’s an antidote to our modern lives a bit. We’re bombarded constantly with information, and we never take time to stop and look inside ourselves and just experience a moment. So I feel like it’s an antidote to that. Making it is an antidote for me,” she explains.

Nothing Gold Can Stay

Justine Giles : 2016 : Written to accompany Albedo

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

To the elements of earth, air, fire and water, Aristotle proposed a fifth element ‘aether’ or ‘quintessence,’ a heavenly substance that made up the celestial bodies and permeated all things. It was a key concept in the belief of the interconnectedness of all things in nature. Quintessence was a notion that paved the way for the possibility that nature could be separated into component parts, and in turn that there was something original and pure at the heart of everything.

Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE) is credited as being the first western scientist, but he lived at a time when philosophy ruled and mysticism was prevalent, and often the boundaries between these disciplines were indistinguishable. Scientists, philosophers, mystics and alchemists found commonality in their curiosity in learning about the world, the cosmos, and the elements of their make up. At the intersection of early science and mysticism sits the Philosopher’s Stone.

There are a number of interpretations of what the Philosopher’s Stone is and none of them are particularly clear. Researchers are left to conclude that it could be interpreted as a literal object, such as a magical talisman; or a secret recipe, such as a theoretical formula. Whatever the nature of the ‘stone’ itself, its purpose was, essentially, purification and this was apparently twofold: the stone was supposed to have the ability to turn base metals into gold, and to grant immortality, interpreted as the purification and restoration of the body, or eternal youth.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Life was beautiful but fleeting; disease and death always just around the corner. Seekers of the Philosopher’s Stone hoped to unlock the mystery of prolonging life. Modern science has a corresponding objective in the study of medicine, used to diagnose, prevent and treat sickness, the outcome of which is higher life expectancy.

In 1972, in the Hunan Province of China, a 2,000 year old coffin was excavated that contained the perfectly preserved body of a woman: “its condition was that of a person who had died only a week before… The colour of the femoral artery was like that of a newly dead person” (Marshall, 2001, p. 3). The condition of the body meant that it was possible to perform an autopsy, and it was observed that the skin was still supple, the internal organs still moist. This was the body of Xin Zhui (also known as Lady Dai or Lady Tai). The scientists involved in her discovery could not explain how this incredible preservation had occurred, however it was noted that her mouth contained a jade amulet and there was a brownish liquid containing mercuric sulphide in the innermost of her three airtight coffins.

The Chinese believed in an equivalent of the Philosopher’s Stone the ‘pill of immortality’ that would allow a person to leave their body and live as an immortal in the afterlife. A sign of its success was to leave behind a body that did not corrupt or decay, a body that could just be sleeping (Marshall, 2001, p. 4). Could preservation in death be seen as equivalent to prolonging life or afterlife?

Readers of fairy tales will be familiar with the idea that no magic spell or talisman works literally in the way that it is expected to. Their promises are trickier than that, keeping an essence of the intention while deftly sidestepping expectation. Immortality here is representational, difficult to verify, and yet mysteriously implied. The search for the perfection of eternal youth is paradoxically an acknowledgement (and rejection) of the fleetingness of life.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

Science at its very beginning was intertwined with magic: “The magician, probing nature’s secrets, served as the template for the scientist.” (Gleick, 2003, p. 104). Alchemists would conjure and discover in equal measures.

The alchemists believed in the interconnectedness of life. Everything was related to everything else in some small way: Matter differed externally only through varying combinations of the four elements: earth, water, air and fire. Therefore, by alchemically manipulating those elements, any kind of matter could be transmuted into another. The conjunction of all elements would produce the philosopher’s stone. (Parry, 2011, p. 9)

Accordingly, all metals were related to all other metals. By this reasoning, if one could only discover the method, the transmutation of base metals into gold must certainly be possible.

John Dee (1527 – 1608) was an advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. They lived in an era where belief in angels and demons was universal, and magic was indistinguishable from science. Elizabeth’s position on the throne was a precarious one in the wake of the reign of her Catholic sister Mary, but had been predicted by Dee through astrology. Elizabeth encouraged Dee’s research, particularly his investigation into the Philosopher’s Stone, as the prolonged life and riches it promised would surely secure her station.

Dee amassed a great library of 4,000 books, and through his research came to believe in a hierarchy of metals with lead at one end, and gold at the other extremity. These metals could be understood as varying combinations of mercury (quicksilver) or sulphur (brimstone). “The elixir would rebalance those principles to purify imperfect metals into gold, remedying Nature’s defects through a process imitating its own creative force” (Parry, 2011, p. 43). Dee’s studies found no conflict between the scientific enquiry of maths and astronomy and the more esoteric investigation into the angelic language of creation, which he believed would bring unity to human kind.

Similarly, Isaac Newton (1642 – 1727) followed both rational and arcane lines of thinking. Newton is better known for his work in the areas of mathematics, physics, calculus and optics, but he was also a keen alchemist: “… alchemy offered Newton, an earnest and devout seeker of truth, a comprehensive philosophy of nature and a unified theory of the universe” (Marshall, 2001, p. 402). Alchemy allowed for religion and science to go hand in hand, it was expected that an investigation into nature would uncover traces of God.

To the modern mind these subjects may seem more difficult to reconcile, but to the alchemists, it was clear. What propelled their education was not so much a search for a solid and singular answer, but a passion for life in all its seething glory “To alchemists nature was alive with process. Matter was active, not passive; vital, not inert” (Gleick, 2003, p. 101), life contained movement, and all nature contained life.

The fatal flaw in the theory of the Philosopher’s Stone was that its two proposed outcomes were both regressive or backwardly inclined: attempts to either create gold or discover eternal youth are, at heart, attempts to reverse the order of nature. Both products require a return to something that is already gone, something that cannot be gained by building, only by stripping away. Gold is not a composite. It can be a component of a composite, but cannot be created where it did not exist to begin with. Similarly, eternal youth requires the regaining of a type of purity lost to age.

These dual quests required distillation rather than creation, a metaphorical return to Eden.

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

What doesn’t make sense is that seekers of the Philosopher’s Stone held up gold as the epitome of perfection, and yet expected that it was possible to make it out of baser things. Likewise it could be seen as nonsensical to expect to reach enlightenment with only a base human to work with.

How could enlightenment be linked to youth when wisdom comes with age?

The ambiguity surrounding the nature of the Stone itself suggests that actually the Stone was of far greater value than the gold it purported to create: after all gold was already known, the Philosopher’s Stone was a mystery. No one knows for sure if the Stone was meant to be a magical amulet or a glorified recipe, and maybe that was because it was neither. Perhaps the Philosopher’s Stone was a symbolic quest, an allegory, intangible and mysterious because it truly only represented the accumulation of wisdom. Perfection is knowledge.

Where science and mysticism diverge is while scientists ultimately must prove or disprove their hypotheses; mystics find greater value in the thought and the search beyond the desire to finitely explain outcomes: Curiosity without cynicism.

On a sheet of paper Newton wrote: “To explain all nature is too difficult a task for any one man or even for any one age. Tis much better to do a little with certainty & leave the rest for others that come after you”(Newton as cited in Gluick, 2003, p. 190).

The great irony is, of course, that if the Philosopher’s Stone is a metaphor, then these alchemists, scientists, obtained it without even knowing: gaining and contributing knowledge (gold) and becoming renowned (immortal) in the process.

References

Brown, J. C. (1913). A history of chemistry: From the earliest times till the present day. London, England: J. & A. Churchill.

Frost, R. (1923). Nothing gold can stay [poem].

Gleick, J. (2003). Isaac Newton. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Marshall, P. (2001). The philosopher’s stone: A quest for the secrets of alchemy. London, England: MacMillan.

Parry, G. (2011). The arch-conjurer of England: John Dee. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.