The Annunciation in Christian Mysticism and Italian Art

This past March my husband and I spent a month in Italy which was something we had been trying to do for the past 7 years. We have a 24 hour flight time from here to Europe so it has to be worthwhile to go all that way, hence taking a month to see as much as we could. I am a huge fan of Barqoue painting and sculpture so there was a lot of Bernini and Caravaggio on our itinerary and I made my husband go to see it all! Luckily, he loves history so there were no complaints. We visited the big galleries such as the Borghese, the Uffizi, the Vatican museums, a special Caravaggio exhibition at Palazzo Barberini and countless churches with incredible artwork collections. One of the great things about Rome is that all churches are free to visit, including St Peters, which is not the case in some of the other major tourist cities.

Churches often have some of the most spectacular artwork, for example St Peters has Michaelagelo’s incredible Pieta as well as a host of Bernini sculptural works including the spectacular 29 meter tall baldachino rising above the high altar and St Peters tomb. The baldachino had been in my mind for so many years and then I finally saw it just this huge sculptural canopy rising into the dome of St peters I was overcome by it’s majesty and the incredible craftsmanship of Bernini. A few other wonderful churches free to visit are Santa Maria della Vittoria, for instance, housing Bernini’s St. Teresa in Ecstasy—a work that has profoundly influenced my understanding of religious art since my university days. In addition, the modest chapel within Santa Maria del Popolo not only displays two major Caravaggio paintings but also exhibits a suite of Bernini’s sculptural pieces. Borromini’s architectural masterpiece, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, is a masterpiece of interior architectural design, it’s simplicity and use of pure white when you have been in a sea of marble baroque extravagance takes your breath away.

Coming back to everyday life I wanted to talk about some aspect of the works I had seen in Italy because I was so moved by being in front of these pieces in real life. For this essay I knew I needed a series of works with an esoteric aspect and I think I’ve got the perfect topic. Its one of my favourite themes from this era –The Annunciation – the biblical event where the Angel Gabriel announces to the Virgin Mary that she will conceive Jesus. This moment holds a profound place in Christian mysticism and given its significance, the Annunciation became a favoured subject in Christian theology, spirituality, and artistic expression from the earliest centuries through the medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque eras. The imagery within these depictions is deeply symbolic and extremely beautiful. In the West, Christian mysticism and esotericism are inextricably entwined and this is particularly so in art from this period where there are many artists were adherents to Christianity but also help interest in esotericism – Leonardo da Vinci an obvious example and one I will be examining in this essay.

I’m going to primarily talk about the symbolism of these works from the biblical point of view and not go into details on the esoteric symbolism. The thing about esoteric symbolism is that it doesnt often benefit from a didactic approach. I think the thing to remember when looking at these is that they are depicting a meeting between the human and the divine. At the heart of it this is the moment when the divine word is made flesh. So keep idea that in mind.

There are certain images and symbols that appear in Annunciation paintings including the gestures and poses of Gabriel and Mary, the symbols of the lily, the dove, the book and the garden. In this essay I will only examine key Italian works from the medieval through to Baroque periods but there are many, many other amazing depictions of the Annunciation throughout European art from these same eras.

Many of these images shown are my photos , in particular the the close-ups, but I’ve also searched online for a few photos of the gallery settings so you can see the size of the paintings as sometimes they are surprisingly large.

This first work is one I saw at the Uffizi gallery in Florence. This is an exquisite gothic altarpiece from 1333 The Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus by Sienese painter Simone Martini with Lippo Memmi. It is one of the earliest landmark Annunciations in Western art. It exemplifies the Gothic style with its elegant, elongated figures and lavish gold background. Gabriel kneels with flowing robes and golden wings leaning towards the Virgin Mary while she appears startled even recoiling slightly and nervously pulling her mantel over her chest. The angels cloak is billowing out behind him suggesting he has just arrived and he kneels, leaning towards Mary in reverence holding out an olive branch symbolising peace and divine favour. Between them sits a luxurious golden vase of lilies which is a symbol used often in Annunciation paintings signalling Mary’s purity. Above the scene in the apex of the central arch is the dove representing the holy spirit. In Luke 1:35, Gabriel tells Mary “the Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Highest will overshadow you” so the dove is usually seen descending from the heights of heaven towards the virgin. In this depiction the dove is sounded by the winged faces of seven cherubim.

I find the stylisation of the faces in this work appear very stern, but it seems typical of this gothic period that the expressions aren’t as natural as they become later, with their long noses and stern expressions making way for a softer countenance. The other very interesting element in this painting is that Gabriel’s words are shown in 3d relief as if they have form. He pronounces "Ave gratia plena Dominus tecum", which translates to "Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with you". This painting was ground breaking in its time for the emotional interaction it portrays and its fine detailing. It set a precedent for showing the drama and divinity of the Annunciation in a single striking image, influencing artists for generations and also establishing visual conventions like the lily and the textual greeting that would recur in later works.

Dominican Fra Angelico’s Annunciation is the next work I would like to share. Unfortunately I didn’t see this work even though it is in Florence because while these works are all in the same city they tend to belong to different churches, palazzos etc We were there for 4 days and you can only see so much which meant that I didn’t get to the Convent of San Marco to see this work which is painted onto one of the walls. This fresco is early Rennasaince around the 1440s and having moved away from the stylisation of medieval art is beginning to take on a naturalistic feel. This fresco is often celebrated for its simplicity, serenity, and peace. It shows Mary and Gabriel in a loggia (a sort of open-air portico), bathed in a soft light. It’s very different from the previous depiction as instead of being set against a flat gold background it is actually showing the meeting of the two figures in a real world setting with depth and perspective. Both figures incline their heads gracefully; Gabriel crosses arms over his chest in reverence, and Mary mirrors the gesture, folding her hands in her lap and modestly crossing her arms in an almost identical manner. There is no overt drama in this scene, only a quiet meeting of two figures in an attitude of mutual humility, which is interesting because its placing Gabriel and Mary – a divine being and a human – on an equal footing. This fresco captures the sacred stillness of the moment with soft colors and gentle expressions as if the angel has just tiptoed in rather than an entrance with a great fanfare.

You may notice that most classic Annunciation symbolism is not present; no lilies, no dove, no sacred texts so if it wasn’t for the halos and Grabriel’s rather lovely coloured wings it could be 2 humans meeting in a loggia, we only know what’s happening here because we know the story. That being said this painting has something the previous one did not but we will see again in later works and this is the walled garden. This motif is drawn from the Song of Solomon 4:12 (“A garden enclosed is my sister, my spouse; a spring shut up, a fountain sealed”), which Christian tradition applied symbolically to Mary’s perpetual virginity. This depiction has been tremendously influential and is considered one of the most beloved Annunciations in sacred ar. It exemplifies the dawn of the Renaissance: integrating realistic understandings of space with medieval devotional clarity.

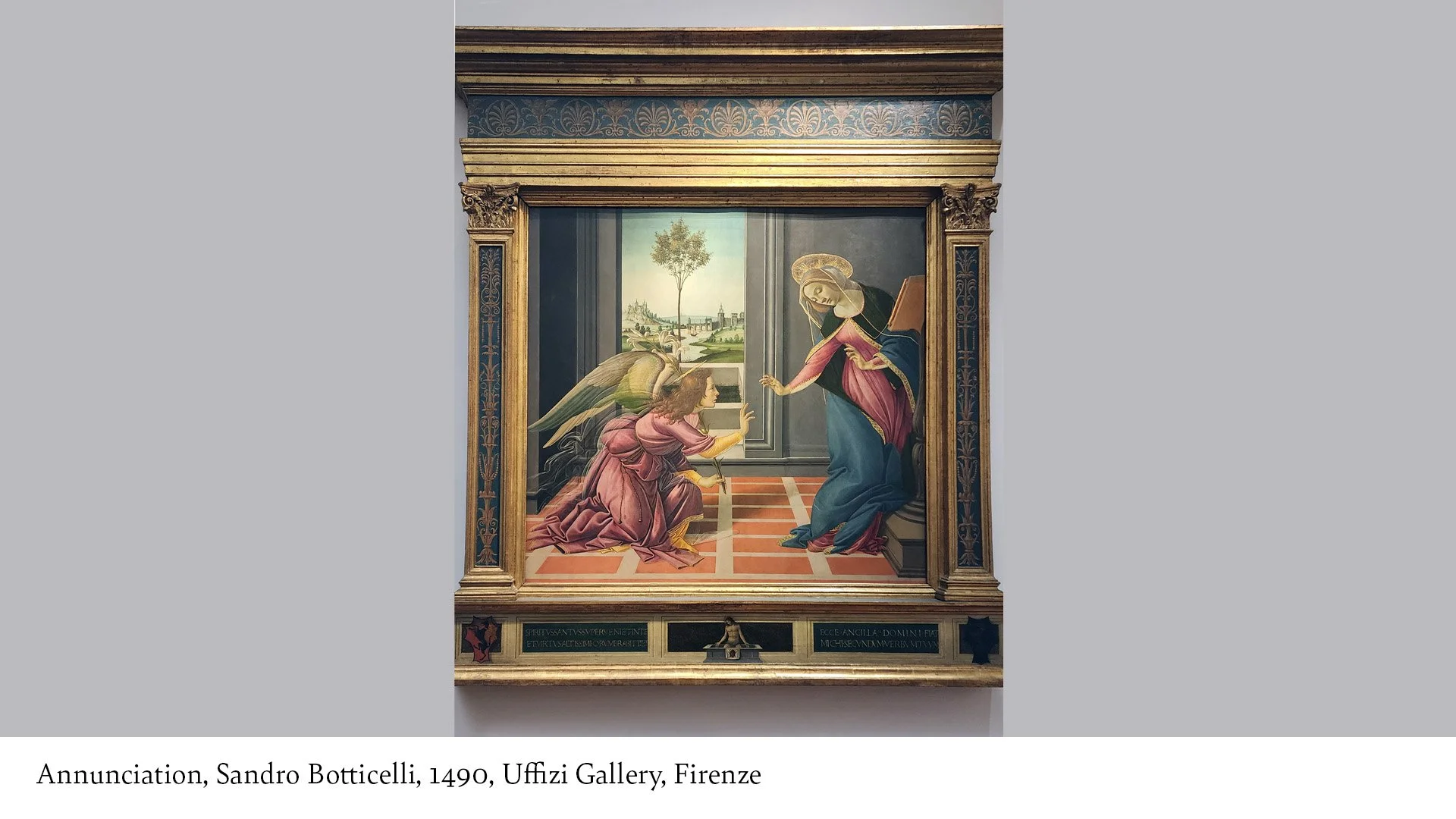

This next work is the very famous Cestello Annunciation from 1490 by Sandro Boticellis Rennaisance. Every time I look at a picture of this from now on I’m going to be disappointed as I have never seen a reproduction that even begins to capture how beautiful this painting is. I always hear about the wonders of The Birth of Venus and the Primavera, but for me this painting surpasses them. Botticelli’s interpretation of the Annunciation epitomizes the graceful, linear style characteristic of the Florentine Early Renaissance. He situates the divine encounter within a refined architectural context that opens onto a serene landscape. In the composition, one observes both the walled garden—a recurring symbol of enclosed, sacred space—and a solitary tree rising prominently above Gabriel’s head. This tree, open to multiple interpretations, strikes me as a symbolic bridge between heaven and earth, evoking the very notion of life itself. Moreover, the tree’s form recalls the “fountain sealed” imagery drawn from the Song of Solomon, reinforcing the dialogue between nature and divine mystery.

The painting’s most arresting quality is found in the gestures of the two central figures. Gabriel is depicted not merely kneeling but bowing in profound reverence as he appears to descend from the celestial realm. In contrast, Mary is portrayed with a gesture of uncertainty or humility—her figure leaning as though on the verge of stepping from the pictorial frame, her downcast eyes and extended arm suggesting both vulnerability and acceptance. The mirroring of the angel’s and the Virgin’s hand, although they do not physically meet, creates a unique spatial focus reminiscent of the dynamic potentiality observed in Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. This interplay of gesture, imbued with an element of theatricality, is typical of Botticelli’s penchant for expressive exaggeration.

Botticelli includes the usual elements of Marian symbolism: one can see an opening in the wall behind the figures, subtly suggesting the “door of heaven” and in the background a walled garden symbolizing Mary’s enclosed virginity. Botticelli’s color palette is restrained with muted blues, pinks, and earth tones. You have probably noticed that colour symbolism plays a large part in these paintings with blue and white for the virgin symbolising her role as the Queen of Heaven and white for her purity. Gabriel often appears in red or pink; red expressing divine power or as a foreshadowing of Christ’s wounds and pink as a symbol of love and grace. The Cestello Annunciation remains one of the-iconic Renaissance interpretations, marrying symbolic depth with the Renaissance era’s attention to naturalism and emotion.

During my Uffizi visit, I also encountered a High Renaissance work from 1472 by Leonardo da Vinci. Although I had previously viewed images of this painting, the experience of seeing it in person was transformative—its beauty evoked an almost overwhelming emotional response as I was struck by the luminosity of the colours and softness of gesture.

Although this work represents an early phase in Leonardo da Vinci’s career, it exemplifies the High Renaissance’s pursuit of naturalism, scientific perspective, and subtle emotion. In Leonardo’s composition, the Virgin Mary is depicted seated outdoors at a meticulously adorned marble table, absorbed in reading when Gabriel appears. The angel presents her with a white lily and offers a gesture reminiscent of a benediction with his outstretched hand. Mary’s demeanor is calm and thoughtful; her body is largely turned toward Gabriel, and one palm is raised in a gesture that suggests mild surprise. While both figures are rendered in a naturalistic manner, certain anomalies are evident—such as the elongated appearance of Mary’s right arm—which may be attributed to the painting’s intended perspective from a slightly lower vantage point, as it was originally conceived for a church altar. Notably, the detailed rendering of the angel—captured in a striking close-up—reveals Leonardo’s study of avian anatomy and his deep attention to botanical details. In this work, the miracle is communicated with quiet elegance: eschewing overt symbols like golden heavenly realms or inscribed texts, the painting instead portrays a serene encounter at dawn in an idyllic landscape, where human and divine meet in a moment of understated revelation.

While in Italy I was lucky enough to experience many amazing works by one of my favourite baroque artists, Carravaggio. This particular depiction of the Annunciation from 1608 was unfortunately not one of them so in this case we have to make do with a picture off the internet. Caravaggio’s interpretation diverges markedly from the Renaissance style. His vision is rendered with a dark, intense, palette. The composition is pared down to its essential elements: only Gabriel and Mary appear against an ominous background, the sole traditional symbol being the lilies that Gabriel carries. Instead of depicting Gabriel as gently kneeling beside Mary, Caravaggio positions him as if hovering in mid-air, looming over the kneeling figure of the Virgin. His figure is foreshortened and projecting toward the viewer in a strikingly illusionistic manner—a technique more characteristic of later Baroque ceiling painting. Meanwhile, Mary is portrayed with her body bowed and her hands clasped tightly across her chest, conveying a realistic, human reaction of apprehension and vulnerability in the face of the divine. The deliberate concealment of Gabriel’s facial features prompts the viewer to wonder at the nature of his countenance and whether that could be what causes Mary to bow her head and lower her eyes. Caravaggio’s signature use of tenebrism is boldly utilised in this work: the angel’s robes and arm are harshly illuminated while the surrounding space is consumed by shadow, endowing the painting with foreboding, perhaps of Christ’s ultimate fate.

Although Caravaggio’s Annunciation may not have attained the renown of some of his other masterpieces, it stands as a pivotal reinterpretation of the theme. Here, the Annunciation is not portrayed as a gentle dialogue but rather as a moment of nearly shocking divine intrusion—emphasizing both Mary’s fear and the angel’s urgent mission. This reimagined portrayal paved

the way for later Baroque artists to depict biblical events with a heightened sense of drama and emotional realism, while still preserving essential iconography such as the angel, the lily, the reticent Virgin, and the motif of divine light. The overall effect is one that is both stark and, at times, disconcerting, yet undeniably filled with wonder. I hope one day to be able to view this painting in person.

It is truly remarkable to observe how depictions of the Annunciation evolved over just a few centuries within Italy.